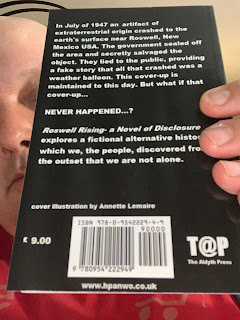

Christmas is coming! I know it's only October, but in the

world of bookselling the season always starts early to catch the present buying

rush. We also have Black Friday before then. For this reason I have created

sales links for all three books of the Roswell Trilogy including QR tags. If

you know anybody who might be interested in copies, or anybody who'd like to

buy them for another person, please share it with them.

Ben's Bookcase

Friday, 24 October 2025

Sunday, 27 October 2024

Redeemed in Months!?

Since the previous mishaps, see background links below, I

have adopted the habit of regularly checking the Amazon pages for the Roswell

See here for background: https://hpanwo-bb.blogspot.com/2021/06/redeemed-available-again.html.

And: https://hpanwo-bb.blogspot.com/2020/08/one-star-for-redeemed.html.

And: https://hpanwo-bb.blogspot.com/2018/07/review-trolls.html.

See here for background: https://hpanwo-bb.blogspot.com/2021/06/redeemed-available-again.html.

And: https://hpanwo-bb.blogspot.com/2020/08/one-star-for-redeemed.html.

And: https://hpanwo-bb.blogspot.com/2018/07/review-trolls.html.

Tuesday, 13 August 2024

The Obscurati Chronicles- Chapter 8

This is Chapter 8 of The Obscurati Chronicles, a novel I am currently serializing. See here for Chapter 7: https://hpanwo-bb.blogspot.com/2023/03/the-obscurati-chronicles-chapter-7.html.

Wilfred Ursall was dreaming. The dream was similar to previous ones, a continuation of them. It was emotionally intense, powerful and highly lucid; as recurrences progressed more details had emerged. It began with Will walking across a plain of cracked, parched soil. The air was freezing cold, but it was also stale and arid. He was wearing only light outdoor clothing and so was shivering; his teeth chattered and his hands became numb. His mouth was caked from microscopic fines, wafted by the lightest of breezes into the air from the desiccated ground. He looked up into the sky; but there was no sky, just a ceiling of smog. It was grey and brown, mottled with cancerous streaks of black, from horizon to horizon. The lifeless sun clawed helplessly through the fume to emerge as a hazy splat of red; heatless and choked, as if drained by the effort it took to rise in the sky. Its height indicated that it was around

Will looked at his surroundings. He was in a smooth shallow valley with a river at the bottom. The edges of the valley were lined by a pair of stone walls with buildings behind them. He was about fifty yards or so from the river and so walked closer to take a look. There was a dozen yards of cracked semi-solidified mud bordering the river, indicating that it was a tidal river, or a river that has just receded from a flood. The soil which displaced with the ease of sand under his shoes gave way to the mud. The mud was thin, pure and clean; there were no pieces wood, waterweed, insects or anything else mixed in with it. The water itself was black and looked viscous, more like oil than water. It gave off a foul stench, like sewage or chemicals, and it looked as lifeless as the sky. The river was only about twenty feet across. He turned away from the river and looked at the walls bordering the valley. They were a dozen or more feet high and looked like they were made of stone. They ran parallel to each other and at one point a few hundred yards along they both jutted out into two broken stumps of masonry directly opposite each other, as if they were the remains of a bridge that once crossed the river. There were tall buildings behind the walls that looked strangely familiar to Will despite the unearthly setting. He walked up the slope of the valley to get a closer look. There were no breaks in the wall, but at odd intervals there were flights of stone steps leading up to the top of it; Will approached one of them. For some reason the steps didn't quite reach the ground and ended about five feet above it. Will had to clamber up onto the bottom step before walking up the rest of them normally. When he reached the top he had a far better view of his surroundings. He stood still and looked around himself and recognized where he was. His heart was thumping and his blood ran far colder than it would have from just the low air temperature. He was standing on the Embankment of the River Thames in central

Will opened his eyes feeling completely awake. He lay alone

in his bed at home, sunlight streaming in through the open window. Cool morning

air filled the bedroom. Lareen was not there and Will could hear Annabelle

chuckling and splashing in the bathroom as her mother bathed her. She must have

been careful not to wake him as she got up. He walked over to the window,

looked out at the garden and took a deep breath. The sun was shining and birds

twittered. Even right now, just after seven-thirty, it was getting warm.

Reality couldn't be more different from his dream. He frowned as he recalled

it. This was the fourth or fifth time he had had a dream like that. What did it

mean? Where did it come from? The crisp morning air put the dream out of his

mind as he walked to Radlett station and caught the train into London Edgware

Road Portsea

Place

Will opened it and

read. The sender's address and handwriting immediately identified them as his

paternal grandmother. Will frowned in curiosity; he was not very close to his

grandmother and they hardly ever exchanged correspondence. He began reading: Dear Wilfred, I know you and I don't often

communicate, but I badly need to speak to you, speak about a matter of enormous

urgency relating to your brother. He has become very closely associated with

Cassius Dewlove. I thought it was just a working relationship, but it's got far

worse than that. He needs our help; he needs YOUR help! Please contact me as

soon as possible. Lots of love. Grandma.

Will sighed and folded the letter. "What do you want me to do about it, Grandma?" he muttered to himself. He pulled out a piece of loose-leaf and began writing a reply.

Will sighed and folded the letter. "What do you want me to do about it, Grandma?" he muttered to himself. He pulled out a piece of loose-leaf and began writing a reply.

He left Lancombe Pond station and walked through the City.

He had agreed to meet with his grandmother at her house and felt some

trepidation. He had not seen Loyl Ursall since the New Year and even then he had

hardly spoken to her. It wasn't that he disliked his grandmother; he didn't. It

was just that they lacked the bond that she and Robin shared. He headed for her

house in Yewfield. He hadn't been there since he was a small child, but

remembered where it was; it hadn't changed much. She greeted him with forced

affection and made him tea. "Wilfred." she implored him. "Can

you help, please? Can you talk to him, make him see sense?"

"I'll

try." he replied after a pause.

She frowned. "You sound unsure."

"Grandma... it's just... I know how terrible Cassius is. However, I cannot force Robin to do anything. If anybody could do something then maybe it would be father." He stopped. He had to be very careful what he said from here. "Grandma, I can't untangle the knot tied many years ago by father and mother. They lowered the drawbridge and rolled out the red carpet for Cassius when Robin and I were mere children, a man who openly abused Robin in front of us all. Robin is totally alienated from father as a result. If father would apologize, make restitution, show Robin a methodology that would prevent such a betrayal from ever happening again; that would be far more influential on my brother than anything I could say... Deep down, Robin really wants his father back."

Loyl sighed. "Then could you speak to your father about that?"

He nodded.

She sighed. "Thank you, Wilfred."

Francis Ursall was delighted to see his elder son and greeted him warmly. He insisted on opening a bottle of Scotch, a habit they had got into since Will had used the method to extract information from him a few months ago. They had a cheery conversation; however, his manner changed when Will raised his grandmother's concerns. Francis frowned. "Why do you say that, Wilfred?"

"Robin needs our help. He's getting too close to Cassius. Their friendship isn't... natural."

"In what way?"

"He hardly ever leaves Cassius' side. He hardly makes a single move without Cassius' approval..."

"Well isn't that to be expected?" snapped Francis. "Robin works for Cassius. He has been given a precious opportunity by Cassius in a very senior position at Dewlove Associates."

"But Cassius is only his boss. I don't spend every waking moment with Netts, do I? Sharing meals, staying over..."

"Robin is not you!" Francis looked away and pretended to rearrange the bottles on the dresser, signalling that he was uncomfortable with the subject.

Will paused. "It's not healthy behaviour for anybody."

"Cassius is not anybody."

"I meant for Robin."

Francis sighed. "Wilfred, I am one hundred percent sure that everything with Robin and Cassius is fine."

Will groaned. "You always say that about everything! Could you please just drop the mindless optimism and listen to me?"

Francis turned back round. "If this was anybody other than Cass, you wouldn't care! You just don't like Cass, don't you?"

"Why should I? Why do you like him so much?"

"Because Cass has been the closest and most supportive friend this family has ever had!"

Will chuckled scornfully. "And how often has he visited you since mother kicked the bucket?" The words were out of his mouth before he realized what a mistake it was to utter them. He winced.

Will's father took a step back and gasped. His cheeks reddened and his eyes bulged. "Do not refer to your mother's death like that!"

Will pondered for a moment whether to back down and apologize or double down; after all it was too late. "Why not, father? That is the exact terminology she used when she talked about your mother's impending death, and she didn't wait till she was dead before doing so!" This was true. Maartje Ursall's hostility for her mother-in-law was a palpable force, almost a solid object. When in her presence Maartje was tight-lipped and stern faced, but when alone with the rest of the family she was very vocal and unabashed about her antipathy. For example, one day after a visit to her house, Francis had expressed on the drive home how much he admired his mother's new dining table. His wife responded grimly "I'm having that when Loyl kicks the bucket." Nobody in the car answered her. Francis showed no discomfort with what Maartje had just said concerning his mother; nor did he at any other time, and she made many similar comments. It became a bit of a maxim of hers. A hundred statements of intention for her began or ended with "...When Loyl kicks the bucket..." She seemed to believe that Loyl's very existence was somehow standing between her and some kind of future utopia. Will was momentarily glad for Maartje's sake that the afterlife didn't exist. It would torment his mother's soul for eternity that her hated mother-in-law had outlived her.

"You ask too much, Wilfred." said Francis. "You cannot expect your mother to live her life according to average standards. She suff..."

"'She suffered so much everyday'!" interrupted Will rolling his eyes. "I know, father! We all know! Why..." He stopped. What was the point of repeating a debate with his father that he had had before. He was tired of wining debates with his father and his father just carrying on oblivious. Will gave up. It was obvious Francis was not going to help him. He felt a wave of sadness as he looked at his father talking to him. Increasingly as time passed, when in the company of his father, he felt a disturbing sense of non-presence. It was as if his father's mind was really some kind of phonograph that just repeated phrases mindlessly. Francis Ursall's eyes looked increasingly blank; not dead and necrotic like Cassius Dewlove's, but functional and flat with no depth behind them, like a cinema picture. Will realized this was not because Francis had changed; he had not developed senility or schizophrenia. It was Will who had changed. He used not to notice this sad absence of personality, but now he did.

Will decided to cut out the middle man and speak to his brother face-to-face. He knew from their brief conversation at their father's Barony ceremony eighteen months earlier that this wouldn't be easy. He had hardly seen Robin since then. He called Dewlove Associates as soon as he arrived inLondon United

States Regents Park six

PM . It was a fine summer afternoon so Will decided to walk from the

Lancine embassy. The rendezvous was in the Inner

Circle

Will didn't reply, wondering if this was a trap. Was this a British agent come to try and expose him?

The stranger smiled, keeping his eyes straight ahead. "Well done, comrade; you are well trained. Fear not. Hargreaves is... unavailable today, so I have come in his place." The man had a different accent, German or Austrian.

"Who are you?" stammered Will.

"My name is... Otto."

Will grimaced thinly, partly from relief and partly from amusement. He knew this was not the man's real name.

What followed was the kind of conversation Will had never imagined he would have with a controller. Otto spoke for a long time about personal and irrelevant matters. "My cousin runs the Odeon cinema chain; did you know that?... I live in the new flats inLawn Road

Will wondered if Otto was psychologically analyzing him.

Eventually Otto got to the point. "Comrade, we are interested in the experience you had in thatBerkshire village. We'd like you to find out

more."

Will chuckled. "You mean the rubber doll?"

Otto paused. "Yes please."

"Seriously?"

Otto raised his eyebrows. "Just some loose ends we'd like to tie up."

"What do you mean?" At once he realized he shouldn't have asked. Agents are not meant to know everything that goes on in the organization they work for.

"Comrade..." began Otto with a frown.

"I know! I know! You can't tell me. Apologies, Comrade Otto."

Otto waved his hand genially to dismiss the matter. "Ask around, find the right people. Catch them when they are vulnerable; like you did with your father."

Will nodded. The meeting ended after that and he went home. He wondered on the journey what on earth that strange conversation was about. He once more pondered the possibility that this was some kind of test. It struck him like a lightning bolt of fear while he was on the train to Radlett; they may suspect he that had been "turned". He bit his nails as that train of thought continued. It all fitted into place. He'd even heard discussions about this at the spy school, although it was not a part of the formal curriculum. Something he had said or done had alerted his controllers and they now were afraid he was secretly working for British intelligence. There were numerous methods of exposing double agents and one of those was to use other agents to plant coded or fake material for him to assimilate and see if he took the bait. Another was to check the quality of the genuine information he was providing against independent sources. One clue an agent might have that he was being scrutinized in this way was that the nature of his handlers' requests suddenly changed. He may be given crazy sounding instructions that appeared to serve no purpose. What could a double agent expect if he were unmasked? Bolshevik counterespionage was notoriously merciless to traitors. They would probably kill him. Will sat back in his seat and breathed deeply, regaining control of his nerves. He reminded himself that he was not a double agent. He was a loyal servant of theSoviet Union , dedicated to the cause of

spreading socialism across the world. The best thing he could do was simply

cooperate with whatever trial his overlords had decided to inflict upon him

until he had proved himself innocent. By the time the train had pulled into

Radlett station his panic was over. He merely felt a frustration that during

this investigation he would be taken away from his main task, being a real spy.

He hoped this wouldn't take too long; and he also wondered what it was about

him that had rung alarm bells in Moscow

She frowned. "You sound unsure."

"Grandma... it's just... I know how terrible Cassius is. However, I cannot force Robin to do anything. If anybody could do something then maybe it would be father." He stopped. He had to be very careful what he said from here. "Grandma, I can't untangle the knot tied many years ago by father and mother. They lowered the drawbridge and rolled out the red carpet for Cassius when Robin and I were mere children, a man who openly abused Robin in front of us all. Robin is totally alienated from father as a result. If father would apologize, make restitution, show Robin a methodology that would prevent such a betrayal from ever happening again; that would be far more influential on my brother than anything I could say... Deep down, Robin really wants his father back."

Loyl sighed. "Then could you speak to your father about that?"

He nodded.

She sighed. "Thank you, Wilfred."

Francis Ursall was delighted to see his elder son and greeted him warmly. He insisted on opening a bottle of Scotch, a habit they had got into since Will had used the method to extract information from him a few months ago. They had a cheery conversation; however, his manner changed when Will raised his grandmother's concerns. Francis frowned. "Why do you say that, Wilfred?"

"Robin needs our help. He's getting too close to Cassius. Their friendship isn't... natural."

"In what way?"

"He hardly ever leaves Cassius' side. He hardly makes a single move without Cassius' approval..."

"Well isn't that to be expected?" snapped Francis. "Robin works for Cassius. He has been given a precious opportunity by Cassius in a very senior position at Dewlove Associates."

"But Cassius is only his boss. I don't spend every waking moment with Netts, do I? Sharing meals, staying over..."

"Robin is not you!" Francis looked away and pretended to rearrange the bottles on the dresser, signalling that he was uncomfortable with the subject.

Will paused. "It's not healthy behaviour for anybody."

"Cassius is not anybody."

"I meant for Robin."

Francis sighed. "Wilfred, I am one hundred percent sure that everything with Robin and Cassius is fine."

Will groaned. "You always say that about everything! Could you please just drop the mindless optimism and listen to me?"

Francis turned back round. "If this was anybody other than Cass, you wouldn't care! You just don't like Cass, don't you?"

"Why should I? Why do you like him so much?"

"Because Cass has been the closest and most supportive friend this family has ever had!"

Will chuckled scornfully. "And how often has he visited you since mother kicked the bucket?" The words were out of his mouth before he realized what a mistake it was to utter them. He winced.

Will's father took a step back and gasped. His cheeks reddened and his eyes bulged. "Do not refer to your mother's death like that!"

Will pondered for a moment whether to back down and apologize or double down; after all it was too late. "Why not, father? That is the exact terminology she used when she talked about your mother's impending death, and she didn't wait till she was dead before doing so!" This was true. Maartje Ursall's hostility for her mother-in-law was a palpable force, almost a solid object. When in her presence Maartje was tight-lipped and stern faced, but when alone with the rest of the family she was very vocal and unabashed about her antipathy. For example, one day after a visit to her house, Francis had expressed on the drive home how much he admired his mother's new dining table. His wife responded grimly "I'm having that when Loyl kicks the bucket." Nobody in the car answered her. Francis showed no discomfort with what Maartje had just said concerning his mother; nor did he at any other time, and she made many similar comments. It became a bit of a maxim of hers. A hundred statements of intention for her began or ended with "...When Loyl kicks the bucket..." She seemed to believe that Loyl's very existence was somehow standing between her and some kind of future utopia. Will was momentarily glad for Maartje's sake that the afterlife didn't exist. It would torment his mother's soul for eternity that her hated mother-in-law had outlived her.

"You ask too much, Wilfred." said Francis. "You cannot expect your mother to live her life according to average standards. She suff..."

"'She suffered so much everyday'!" interrupted Will rolling his eyes. "I know, father! We all know! Why..." He stopped. What was the point of repeating a debate with his father that he had had before. He was tired of wining debates with his father and his father just carrying on oblivious. Will gave up. It was obvious Francis was not going to help him. He felt a wave of sadness as he looked at his father talking to him. Increasingly as time passed, when in the company of his father, he felt a disturbing sense of non-presence. It was as if his father's mind was really some kind of phonograph that just repeated phrases mindlessly. Francis Ursall's eyes looked increasingly blank; not dead and necrotic like Cassius Dewlove's, but functional and flat with no depth behind them, like a cinema picture. Will realized this was not because Francis had changed; he had not developed senility or schizophrenia. It was Will who had changed. He used not to notice this sad absence of personality, but now he did.

Will decided to cut out the middle man and speak to his brother face-to-face. He knew from their brief conversation at their father's Barony ceremony eighteen months earlier that this wouldn't be easy. He had hardly seen Robin since then. He called Dewlove Associates as soon as he arrived in

Will didn't reply, wondering if this was a trap. Was this a British agent come to try and expose him?

The stranger smiled, keeping his eyes straight ahead. "Well done, comrade; you are well trained. Fear not. Hargreaves is... unavailable today, so I have come in his place." The man had a different accent, German or Austrian.

"Who are you?" stammered Will.

"My name is... Otto."

Will grimaced thinly, partly from relief and partly from amusement. He knew this was not the man's real name.

What followed was the kind of conversation Will had never imagined he would have with a controller. Otto spoke for a long time about personal and irrelevant matters. "My cousin runs the Odeon cinema chain; did you know that?... I live in the new flats in

Will wondered if Otto was psychologically analyzing him.

Eventually Otto got to the point. "Comrade, we are interested in the experience you had in that

Will chuckled. "You mean the rubber doll?"

Otto paused. "Yes please."

"Seriously?"

Otto raised his eyebrows. "Just some loose ends we'd like to tie up."

"What do you mean?" At once he realized he shouldn't have asked. Agents are not meant to know everything that goes on in the organization they work for.

"Comrade..." began Otto with a frown.

"I know! I know! You can't tell me. Apologies, Comrade Otto."

Otto waved his hand genially to dismiss the matter. "Ask around, find the right people. Catch them when they are vulnerable; like you did with your father."

Will nodded. The meeting ended after that and he went home. He wondered on the journey what on earth that strange conversation was about. He once more pondered the possibility that this was some kind of test. It struck him like a lightning bolt of fear while he was on the train to Radlett; they may suspect he that had been "turned". He bit his nails as that train of thought continued. It all fitted into place. He'd even heard discussions about this at the spy school, although it was not a part of the formal curriculum. Something he had said or done had alerted his controllers and they now were afraid he was secretly working for British intelligence. There were numerous methods of exposing double agents and one of those was to use other agents to plant coded or fake material for him to assimilate and see if he took the bait. Another was to check the quality of the genuine information he was providing against independent sources. One clue an agent might have that he was being scrutinized in this way was that the nature of his handlers' requests suddenly changed. He may be given crazy sounding instructions that appeared to serve no purpose. What could a double agent expect if he were unmasked? Bolshevik counterespionage was notoriously merciless to traitors. They would probably kill him. Will sat back in his seat and breathed deeply, regaining control of his nerves. He reminded himself that he was not a double agent. He was a loyal servant of the

Will sighed as he saw his father's writing on the envelope.

He opened it. Dear Wilfred. Could you

please respond as soon as possible? Mabel and I are very worried. We both found

your behaviour last week upsetting and baffling. Mabel felt very intimidated by

you. You perhaps don't realize why you said what you did... Francis Ursall

waffled on for a few more sentences. The previous week Wilfred had walked out

of Mabel's house in West Bridgford after an explosive

argument. Francis had invited his son to join him for dinner with Mabel. It had

started pleasantly enough. They made casual conversation with each other and

two of Mabel's sisters who had also turned up, but it didn't take long for

tensions to rise. Francis spotted it long before anybody else did. He had a

hair trigger warning sense of anything that might rock the boat, throw

normality off its groove and generate "hassle". He stiffened up and

started interjecting obtrusively into people's conversations. He regularly did

this, appointing himself an informal chairman or moderator in any social

situation. If the smooth train of interaction even threatened to drift off the

tracks into uncomfortable subjects he would blurt out "Let's not talk

about that now please!" raising his hands sideways in his typical

pacifying gesture. Francis was a man addicted to the status quo. Within it he

found comfort and stability. Maintaining it was his only goal. He prioritized

it even above the life and safety of himself and his family. Will recalled the

incident at his grandparents' home with the faulty boiler. If somebody in a

social situation handed Francis a bottle labelled "poison" he would drink

it eagerly just to prove that "everything is a hundred percent fine!"

Will also realized soon after meeting Mabel that his father had not done what

Will had predicted. Will had assumed Francis would find some unspoken

liberation with his wife's death, but he had just gone out and searched for

another woman as domineering and controlling as Maartje Ursall. Although the

nature of Mabel and Francis' relationship was uncertain to all but themselves,

they acted like a romantic couple. Maybe it was another part of the

psychopathology epidemic within the bourgeoisie, but Will realized that the

promise of being bossed around by a woman was the very thing that attracted

Francis to Mabel. It was a huge turn-on.

The problems began

when Mabel started talking enthusiastically about a book she had recently read,

Pan-Europa by the Austrian aristocrat

Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi. "I've got the first English

translation." she bubbled. "It's amazing! It proposes that Europe

should no longer consist of separate countries, warring and competing. Instead

we should become a political federation, like the United

States

"How likely is that to happen?" asked her older sister.

"It will take a few decades, Marge; but one day it will happen. It will probably be called the 'European Union'. Imagine how powerful and prosperous such an empire would be."

If Will had been in a position to speak sincerely he could have said a lot about the benefits of such integration for the purposes of the socialist revolution, but he knew he had to play the part of the little Englander. "I think that sounds awful, Mabel." he put in. "It will probably turn into some kind of dictatorship, offering no freedom of choice to its citizens and will put their culture at risk. If there were ever a referendum allowing us the choice to remain within or leave such a regime I would vote leave."

Mabel turned to Will with a savage scowl. She bared her teeth and her close-set eyes gleamed so much with irritation that they seemed to turn into a single beam, a lighthouse of primitive rage. "What would you know!?... You've never run a business, Wilfred!"

"So what would you say to somebody who had run a business and agreed with me?"

"I doubt if that would happen." Mabel replied.

"Well then you have an unfalsifiable hypothesis, which is a fallacy. All I have to do is produce one person on my side who is qualified to comment, according to your standards, and you are proved wrong. You also made an ad hominem attack which is another fallacy..."

Mabel interrupted with a screeching proclamation. "Anybody who would vote to leave the European Union is stupid!"

Francis Ursall did not even pause for a second before interjecting: "Let's talk about the play we went to see on Saturday..."

As his father droned on, Will was burning inside. The sheer arrogance and injustice of Mabel's attitude cut him like a blade. She had said absolutely nothing to refute Will's points at all. She had begun by discrediting him personally and then called him stupid; and what was worse was that she seemed unaware or uncaring about her own dishonesty. Will stood up. "Right... erm... I shall wish you all a pleasant day and be off."

"What?" breathed his father with a look of terrified dread. "You're leaving?"

"Yes, I'm going to spend the rest of the day with people who don't insult me. Goodbye." He walked towards the door without looking back. Nobody said a word and he did not see Mabel's expression. Predictably his father chased after him. "Wilfred! Wilfred! Please come back!"

"Why, father?" Wilfred shrugged on his coat.

"Mabel was just being forthright."

"Forthright?... No, she was being downright rude and you sat there like a bloody sheep, as usual, and said nothing to support me."

"Please, Wilfred! Don't leave! Come back!"

Will looked into his father's eyes and saw genuine terror. Francis had literally fallen off a social cliff. He sighed. "Father, I'll stay on one condition; you stand up to Mabel. You defend me! We go in there together, right now, and you tell her in front of me and everybody else that she was out of order with what she said to me."

The look in Francis' eyes at that moment filled Will with a mixture of incredible contempt and pity. "Wilfred..." he whimpered. "I can't!"

"Then I'm going." Will replied quietly and walked through the door.

"Christ!" hissed Francis and he collapsed to his knees, burying his knuckles into his eye sockets.

Before he boarded the train home he stopped at the station post office and penned a letter to Mabel. He was so filled with energetic fury that he felt he could do nothing more until he had finished writing. Dear Mabel. Obviously we disagree on the whole European integration issue... He then explained his feelings at her reaction to his dissent. He scribbled on. Regarding your general conduct towards me, it goes beyond just debating one issue. Nobody is a rubber ball that you can just toss against a brick wall again and again in the reassurance that it will not break; although some members of my family pretend that I am just such. Maybe this has led you into the delusion that I am. This may explain your disgraceful behaviour towards Robin at Christmas... This referred to the moment when Will first began to have serious concerns regarding Mabel. Like many families, the Ursalls had a tradition that they all got together on Christmas Day for a celebration and the renewing or reinforcing of their relationships. This usually took place in the Ursall house inEast

Mansfield , and Will and his family attended as usual. The

atmosphere was tense from the offset. Loyl did not turn up; in fact she had

avoided all family gatherings for the last two years. Nobody seemed to mind and

Francis in particular was forcibly nonchalant about the absence of his mother.

Her replacement, if you could call him that, was Cassius Dewlove. He

accompanied Robin unannounced. Nobody objected, especially once he started

skilfully waving his charm around like he always did. Francis was overjoyed to

see Cassius, as he always was. He trotted around him all through the pre-dinner

drinks like a besotted dog. After the turkey and plum pudding they retired to

the lounge where the next part of the Ursall Christmas tradition took place,

the passing around of gifts. Over the course of the festive season a pile of

presents grew up under the Christmas tree, all wrapped neatly in coloured paper

and labelled with the recipient's and donor's names; glowing with enjoyment

potential. Then Francis sat in a corner and handed them out one at a time. He

kept a large rubbish sack beside him to collect the waste paper so that it

wouldn't be scattered on the floor, possibly being mixed up with the actual

gifts. It was a precious annual half-hour period where everybody smiled and

nobody frowned. Francis pulled an oblong parcel wrapped in red crepe paper. He

looked at the label. "From Robin to Mabel." He passed it over to his

friend.

Mabel opened it. It was a book. "What's this?... Stories from the Stars- an Anthology."

"It's a series of tales about adventures in space." explained Robin.

Mabel flicked through it for a few seconds. Then she scowled with affront. "Oh, no thank you!" She tossed it onto the coffee table. Nobody flinched. Francis remained smiling; it was as if nothing happened. Robin also showed no offence; he and Dewlove swapped glances, giving each other half smiles.

Will remained outwardly composed, but inside he was infuriated and horrified. He kept his emotions in check with great difficulty. Lareen was the only one who spotted his inner pain and put her hand over his. After the relatives and close friends had started to disperse to their homes or hotels, Will got the chance to speak to his father alone. Francis was slightly drunk and had stepped out into the back garden for a breath of fresh air and a cigar. Will followed him and unloaded. His father retorted "Wilfred, why is this a problem? Mabel was just being forthright. She didn't want the present and said so."

"No, she tossed it onto the table as if it were a tray of shit! She did it in a very insulting manner and she did it in front of everybody in the family! How dare she!?... HOW DARE SHE!?"

Francis blushed. "Don't swear in this house please, Wilfred!"

"Since when has it been acceptable to behave like that? We both know that if Robin or I had done that to her you would have been mortified! The Christmas party is supposed to be a happy time of family intimacy and Mabel has violated that! And your only response is to try and normalize it!"

His father hissed through his teeth. "I think you need to show a little bit more tolerance, Wilfred. You may not be aware, but Mabel's husband used to mistreat her badly and..."

Wilfred groaned. "And don't tell me! She had a bad upbringing too!"

"Life with other people is not all sweetness and sunshine, you know, Wilfred. And you are the only one complaining here. Robin didn't seem to mind at all, did he?"

"That's because he's been brainwashed by Dewlove!" shouted Will.

"Do not accuse Cassius like that!..."

He had left after that, strutting away and seething in frustration. That had been over six months ago. The quarrel inWest Bridgford was last week. He

read the letter again and then folded it back into his envelope. He went to his

study and began to attempt a reply. ...Father,

why will you not simply admit that this family keeps two sets of books? Robin

and I are the silent generation; we are not permitted to speak. I never heard

you tell mother when she fell out with Briggs "Briggs found your behaviour

upsetting and baffling. He feels very intimidated by you." No! It's only

bad when Robin and I do it! We are always the bad guys in every situation like

this. With mother or the Dutch family their upset was always endorsed and taken

seriously; it used to be the central issue of the entire family until it was

resolved. You have never explained to us why this double standard exists,

never!... Will put his own letter in an envelope and opened his desk drawer

to find a stamp. As he posted the letter he felt an almost overwhelming sense

of relief. The previous six days had been very unpleasant. Being apart from

Francis, incommunicado, had been mental torture. He hadn't expected that. The

reason was obvious, but it still surprised him. Will still cared very much for

his father; but his feelings were different from what they used to be. He felt

almost protective towards Francis, as if it were now his job to take care of

him.

Will was very relieved to receive another letter from his father two days later that was reconciliatory in tone. Francis made it clear that he wanted badly to maintain his relationship with his son aside from "your break with Mabel". Will wondered what he meant until he looked at a second letter in the same post from Mabel. Its tone was very different: Wilfred, I will no longer be visiting your home or your family home inEast Mansfield whenever you or your family are present.

You are not welcome in my home... She went on expressing her affront and

indignation for a few more sentences. She even accused him of threatening her,

which he had not done. Will shrugged as he read, but was surprised. He knew

Mabel would be unhappy with his walkout the previous week, but he had not

expected the ferocity of her reaction. She also showed a complete lack of

introspection. It did not occur to her to question her own role in this

conflict. All she understood was that Will had been hostile to her, she was on

the side of the good and he was on the side of the bad. It was a dismayingly

simplistic and egotistical way to interpret the incident. She was about forty-five

years old, like Francis, but her letter reminded him of a scorned teenage girl.

Will felt a huge amount of relief. He had reconnected with his father and had

not backed down to Mabel. He was determined not to apologize to her. He knew he

had done nothing to feel ashamed of and now that he had released the anger he

had been bottling up for half a year, a surge of liberation flowed though him.

He patted Annabelle on the head and smiled to himself. He looked down at her as

she ate her breakfast rusks and then over to his wife. He was free and

empowered.

"How likely is that to happen?" asked her older sister.

"It will take a few decades, Marge; but one day it will happen. It will probably be called the 'European Union'. Imagine how powerful and prosperous such an empire would be."

If Will had been in a position to speak sincerely he could have said a lot about the benefits of such integration for the purposes of the socialist revolution, but he knew he had to play the part of the little Englander. "I think that sounds awful, Mabel." he put in. "It will probably turn into some kind of dictatorship, offering no freedom of choice to its citizens and will put their culture at risk. If there were ever a referendum allowing us the choice to remain within or leave such a regime I would vote leave."

Mabel turned to Will with a savage scowl. She bared her teeth and her close-set eyes gleamed so much with irritation that they seemed to turn into a single beam, a lighthouse of primitive rage. "What would you know!?... You've never run a business, Wilfred!"

"So what would you say to somebody who had run a business and agreed with me?"

"I doubt if that would happen." Mabel replied.

"Well then you have an unfalsifiable hypothesis, which is a fallacy. All I have to do is produce one person on my side who is qualified to comment, according to your standards, and you are proved wrong. You also made an ad hominem attack which is another fallacy..."

Mabel interrupted with a screeching proclamation. "Anybody who would vote to leave the European Union is stupid!"

Francis Ursall did not even pause for a second before interjecting: "Let's talk about the play we went to see on Saturday..."

As his father droned on, Will was burning inside. The sheer arrogance and injustice of Mabel's attitude cut him like a blade. She had said absolutely nothing to refute Will's points at all. She had begun by discrediting him personally and then called him stupid; and what was worse was that she seemed unaware or uncaring about her own dishonesty. Will stood up. "Right... erm... I shall wish you all a pleasant day and be off."

"What?" breathed his father with a look of terrified dread. "You're leaving?"

"Yes, I'm going to spend the rest of the day with people who don't insult me. Goodbye." He walked towards the door without looking back. Nobody said a word and he did not see Mabel's expression. Predictably his father chased after him. "Wilfred! Wilfred! Please come back!"

"Why, father?" Wilfred shrugged on his coat.

"Mabel was just being forthright."

"Forthright?... No, she was being downright rude and you sat there like a bloody sheep, as usual, and said nothing to support me."

"Please, Wilfred! Don't leave! Come back!"

Will looked into his father's eyes and saw genuine terror. Francis had literally fallen off a social cliff. He sighed. "Father, I'll stay on one condition; you stand up to Mabel. You defend me! We go in there together, right now, and you tell her in front of me and everybody else that she was out of order with what she said to me."

The look in Francis' eyes at that moment filled Will with a mixture of incredible contempt and pity. "Wilfred..." he whimpered. "I can't!"

"Then I'm going." Will replied quietly and walked through the door.

"Christ!" hissed Francis and he collapsed to his knees, burying his knuckles into his eye sockets.

Before he boarded the train home he stopped at the station post office and penned a letter to Mabel. He was so filled with energetic fury that he felt he could do nothing more until he had finished writing. Dear Mabel. Obviously we disagree on the whole European integration issue... He then explained his feelings at her reaction to his dissent. He scribbled on. Regarding your general conduct towards me, it goes beyond just debating one issue. Nobody is a rubber ball that you can just toss against a brick wall again and again in the reassurance that it will not break; although some members of my family pretend that I am just such. Maybe this has led you into the delusion that I am. This may explain your disgraceful behaviour towards Robin at Christmas... This referred to the moment when Will first began to have serious concerns regarding Mabel. Like many families, the Ursalls had a tradition that they all got together on Christmas Day for a celebration and the renewing or reinforcing of their relationships. This usually took place in the Ursall house in

Mabel opened it. It was a book. "What's this?... Stories from the Stars- an Anthology."

"It's a series of tales about adventures in space." explained Robin.

Mabel flicked through it for a few seconds. Then she scowled with affront. "Oh, no thank you!" She tossed it onto the coffee table. Nobody flinched. Francis remained smiling; it was as if nothing happened. Robin also showed no offence; he and Dewlove swapped glances, giving each other half smiles.

Will remained outwardly composed, but inside he was infuriated and horrified. He kept his emotions in check with great difficulty. Lareen was the only one who spotted his inner pain and put her hand over his. After the relatives and close friends had started to disperse to their homes or hotels, Will got the chance to speak to his father alone. Francis was slightly drunk and had stepped out into the back garden for a breath of fresh air and a cigar. Will followed him and unloaded. His father retorted "Wilfred, why is this a problem? Mabel was just being forthright. She didn't want the present and said so."

"No, she tossed it onto the table as if it were a tray of shit! She did it in a very insulting manner and she did it in front of everybody in the family! How dare she!?... HOW DARE SHE!?"

Francis blushed. "Don't swear in this house please, Wilfred!"

"Since when has it been acceptable to behave like that? We both know that if Robin or I had done that to her you would have been mortified! The Christmas party is supposed to be a happy time of family intimacy and Mabel has violated that! And your only response is to try and normalize it!"

His father hissed through his teeth. "I think you need to show a little bit more tolerance, Wilfred. You may not be aware, but Mabel's husband used to mistreat her badly and..."

Wilfred groaned. "And don't tell me! She had a bad upbringing too!"

"Life with other people is not all sweetness and sunshine, you know, Wilfred. And you are the only one complaining here. Robin didn't seem to mind at all, did he?"

"That's because he's been brainwashed by Dewlove!" shouted Will.

"Do not accuse Cassius like that!..."

He had left after that, strutting away and seething in frustration. That had been over six months ago. The quarrel in

Will was very relieved to receive another letter from his father two days later that was reconciliatory in tone. Francis made it clear that he wanted badly to maintain his relationship with his son aside from "your break with Mabel". Will wondered what he meant until he looked at a second letter in the same post from Mabel. Its tone was very different: Wilfred, I will no longer be visiting your home or your family home in

In September 1923 Will was recalled to Lancombe Pond for a week,

for a training session and appraisal. One day, while he had an afternoon off,

he decided spontaneously to pay a visit to his grandmother. This was not

something he ever planned or contemplated before. The reason why, he surmised,

was that his partisan position on the family political landscape had shifted

since his clash with Mabel. He was now more on Loyl's side than he had been

previously. This same process had also brought him closer to Robin. The two brothers

had even met once during the last two months and had exchanged letters. After

some contemplation he decided not to do what his grandmother had asked. He had

already questioned Robin about his friendship with Cassius Dewlove and it had

been a waste of effort. The only hope for his brother, as it was for the entire

bourgeoisie suffering from their self-generated debauchery, was the revolution.

Only socialism could save him now. He entered Loyl Ursall's street and

approached her front door. He rapped the door knocker and waited. There was a

long silence and then he heard somebody moving around inside. He expected the

door to open, but it didn't. This was strange. His grandmother's home was

small; it shouldn't take long for her to get to the door. He frowned and

knocked again. After another few seconds he called out. "Grandma?...

Grandma, are you there?"

The latch clicked

and the door opened slightly. Loyl's face peeped through. "Wilfred... What

do you want?" She was almost whispering.

He had never heard her speak like that. "Er... I was just passing and wondered if you were in?... To be honest, I sometimes feel you're the only real contact I have with this family."

She paused and then opened the door with a sigh. "I'm sorry, Wilfred, I'm about to go out... But do come in."

Will entered the property and saw two large leather suitcases placed on the floor of the lounge. Loyl was dressed for travel, with thick stockings under her knee-length woollen skirt and a cardigan. A coat was draped over one of the suitcases. "Are you going out for a long time?"

"I'm... er... going for a little holiday in Skegness; just a few days." She avoided his gaze.

Will noticed an oblong mark on the far wall showing where a picture frame had once hung. He recalled that it was a photograph of her parents, his great-grandparents, Jesse and Freda Jerkson. She treasured it enormously. He pointed at it. "Grandma... are you taking that with you on holiday?"

She looked at the wall and blushed. "Erm... no, Wilfred. The frame cracked so I've taken it to Cartwright's to get it fixed." There was a long silence. "Wilfred, could you excuse me. I have to go in a minute and need to get ready."

"Of course. Goodbye, Grandma. Have a good trip."

"Goodbye Wilfred. Thank you." She slammed the door urgently behind him as he left. As he walked away down the road in Yewfield he saw a tall white-haired man approaching on the opposite pavement. This street did not have a high volume of traffic because it was a cul-de-sac in a residential area. Nobody entered it except for the purposes of access. The man was walking quickly and with a focused gaze. He appeared not to notice Will. He was carrying a large suitcase and wore a rucksack as if heading off on holiday. Will stopped as he realized the man looked familiar. He crouched behind a parked car to watch the man covertly. Robin used to have a friend who looked very like the man walking up the street, although Will could not remember his name. He was a Dutchman who worked at the hospital inNottingham and he had been at

his mother's funeral in 1919. The man stopped at Loyl's house and knocked on

the door. Will gasped as the door opened and the man entered immediately, as if

his grandmother knew him and had been expecting him. He heard the click as the

door shut. Will turned and kept walking. He shrugged; her life was her own

business. However, he vacillated between amusement and shock at the thought

that his seventy-three year old grandmother might be about to indulge in a dirty

weekend. He giggled to himself.

He had never heard her speak like that. "Er... I was just passing and wondered if you were in?... To be honest, I sometimes feel you're the only real contact I have with this family."

She paused and then opened the door with a sigh. "I'm sorry, Wilfred, I'm about to go out... But do come in."

Will entered the property and saw two large leather suitcases placed on the floor of the lounge. Loyl was dressed for travel, with thick stockings under her knee-length woollen skirt and a cardigan. A coat was draped over one of the suitcases. "Are you going out for a long time?"

"I'm... er... going for a little holiday in Skegness; just a few days." She avoided his gaze.

Will noticed an oblong mark on the far wall showing where a picture frame had once hung. He recalled that it was a photograph of her parents, his great-grandparents, Jesse and Freda Jerkson. She treasured it enormously. He pointed at it. "Grandma... are you taking that with you on holiday?"

She looked at the wall and blushed. "Erm... no, Wilfred. The frame cracked so I've taken it to Cartwright's to get it fixed." There was a long silence. "Wilfred, could you excuse me. I have to go in a minute and need to get ready."

"Of course. Goodbye, Grandma. Have a good trip."

"Goodbye Wilfred. Thank you." She slammed the door urgently behind him as he left. As he walked away down the road in Yewfield he saw a tall white-haired man approaching on the opposite pavement. This street did not have a high volume of traffic because it was a cul-de-sac in a residential area. Nobody entered it except for the purposes of access. The man was walking quickly and with a focused gaze. He appeared not to notice Will. He was carrying a large suitcase and wore a rucksack as if heading off on holiday. Will stopped as he realized the man looked familiar. He crouched behind a parked car to watch the man covertly. Robin used to have a friend who looked very like the man walking up the street, although Will could not remember his name. He was a Dutchman who worked at the hospital in

Will left his home at 7.45 AM

and walked to Radlett station. He stood on the packed commuter train all the

way to Kings Cross and then stopped at a cafe on Tottenham Court Road for a cup

of tea. Before he stood up to pay and leave he placed two teaspoons in the used

cup. He didn't know who was watching him, but he knew somebody was. The signal

worked every time and sure enough at 3.15 PM

Hargreaves showed up at the rendezvous, ten minutes after Will; at the moment

it was in a garden square in Pentonville. It was a warm October afternoon and dry

leaves rustled like shingle in the light breeze. "I managed to get it out

of Eveslowe last night." began Will as soon as his controller had sat on

the bench. "He was pretty squiffed at the In and Out. He says it's all

true, but they're not from Mars."

"Where are

they from?"

"Nobody knows, or at least Eveslowe doesn't." The whole process had taken about a month. Hargreaves gave him additional coaching to select the perfect target. Somebody quite old and senior with military connections, a few personal secrets and as many vices as possible. Col. David Eveslowe had recently retired from the War Ministry and regularly indulged in more than his fair share of brandy and cigars. He had spent twenty years inIndia Rawalpindi Sandhurst

accent to match; a portrait of a typical British imperialist. He was wearing

his well laundered dining jacket, although it showed the wear and tear of hard

socializing. A Persian rug of medal ribbons adorned his breast. Within an hour

of their conversation Will was fairly convinced the old man was a homosexual;

another important qualification for the list. Will told Hargreaves there was no

way he'd be able to seduce Eveslowe, and the handler laughed and reassured him

that would not be necessary. Instead all he had to do was be friendly and happy

to listen for a long time to the old army officer's tipsy ramblings. Within a

few days they were de facto friends

and Will dropped in to see him after that about three times a week. They told

each other all kinds of stories about each other over drinks and dinner. The

Colonel was clearly enjoying the attention this handsome young man was giving

him and was eager to maintain it. After about three weeks Will spotted an

article in The Times while he was

reading it on one of the leather settees; it was about a new observatory being

constructed in Yorkshire . This was his opportunity.

"Dave, old boy." he said. "Take a look." He handed his

contact the paper.

"Ah!" Eveslowe puffed on aHavana

"It's a pity we don't have a telescope here, Dave."

"Perhaps we should get one installed in the garden. I'll suggest it to Patel... How many stars can we actually see in the middle of the Smoke anyway? Let's go and have a look." He clambered shakily to his feet. It was now9 PM and he had polished off half a bottle of Remy Martin.

He and Will walked out into the empty courtyard. He looked up. "Bah! Too

much streetlight and smog."

"What a pity." sighed Will in the same tone. "I love the sight of a clear night's sky, cloudless and pure."

"I know, Wilfred, I know. InIndia

Now was the moment for his next move. "You should be a poet!... I say, Dave... Do you suppose there's anybody out there, looking back at us?"

He laughed. "Oh certainly, old boy!"

"Certainly? You have no doubt?"

Eveslowe looked at him in a fatherly way without desire. "None whatsoever, dear boy. You see... No, no, no; I really can't tell you."

Will put on his best frown of curiosity. "What do you mean, Dave?"

He hissed through his teeth in an intoxicated expression of awkwardness. "We have proof, Wilfred."

"Does this have anything to do with what's going on at Peasemore?"

The old man gasped and took a step back. His face flushed as if Will had struck him. "Wilfred... where did you hear about that?"

He shrugged modestly. "Word gets around."

Hargreaves watched a starling pecking the path near his feet. "And did he tell you more?"

"Yes." Will related some more details for a few minutes.

The controller suddenly stood up. "Let's take a walk, Comrade Ursall."

"What?" Will stood up beside him. This had never happened before. Contact with his controllers had always been stationary and in a public yet secluded place. In fact at the spy school he'd been warned about movement, that it could look suspicious in the wrong circumstances. "Comrade Hargreaves. I think we're supposed to remain seated during our conversations..."

"This is an unusual occasion, Comrade Ursall." Hargreaves lifted his right arm in which he carried a copy of The Times. It was draped over his wrist and was arranged in such a way that only Will could see the pistol clasped in his hand.

"No!" yelled Will and jerked back.

"Keep your voice down and stand still!" commanded Hargreaves in a voice only slightly raised. "Now, walk towards theSt John Street

Will nodded. He was panting hard and his legs felt weak, but he did what his controller said. A car, a non-descript Morris, was waiting by the gate with two men in the front seats. Its rain cover was up. "Get in." said Hargreaves. The agent and controller sat beside each other in the back seat. Will was about to look at the two other occupants when a hood was roughly tugged over his head totally obscuring his vision. His heavy breathing became more laboured through its textile. "Calm down, Comrade Ursall. You are in no danger."

"Having a gun pointed at me is not exactly safe!" protested Will.

"Sorry about that, comrade; it was necessary." The car drove for about half an hour although, of course, Will could not be completely sure of the time. At one point Will heard the ambient sounds that leaked in change in a way that gave him the impression they were crossing one of the bridges over the river. He hoped they were heading for the Soviet embassy in Kensington, in which case this would be a happier situation. On the other hand this action against him by his handlers could be something less official and therefore probably more violent. This was exactly what Will had feared. They had tested him and he'd failed. The worst part was that he knew he was innocent. Could he persuade them? He was afraid they would torture him, in which case he knew that he would eventually say anything they wanted him to. Or maybe they had already made up their minds, in which case...

"Alright, we're there." said a new voice from the front seat. The car turned a few times and then stopped. "Let me guide you, comrade." said Hargreaves. Will got out of the car with the blindfold still over his head and walked with Hargreaves holding his arm. "There are four steps up here... That's it." A few yards further the handler ordered him to sit.

Hargreaves pulled off the hood and all Will's senses were assailed at once. He was sitting at a small wooden table in an office of some kind. There was a cardboard calendar on the wall, a filing cabinet and a pair of desks facing each other. The wall was painted dark brown and the windows looked out onto a street with a red brick wall opposite, although Will couldn't make out many of the details until his eyes had adjusted to the glare. Sitting around the table scrutinizing him were Hargreaves, Otto and a third man whom Will had never before seen. Hargreaves had laid the pistol on the table, but his hand rested on it; a silent warning to Will not to try and flee. Despite the nature of his presence there, the men were all smiling. "Would anybody like some vodka?" asked the stranger. He had a Russian accent and a big bald military look to him.

"Four glasses please, Yuri." replied Otto. After the drinks were all poured he raised his. "Vashe zdorov'ye."

"An kkomyt." Will replied and took a sip. He felt calmer now and slightly rebellious. He had learned enough at spy school to realize now that these men would not do him any grievous bodily harm, at least not at this meeting. A round of vodka meant a little chat, not a beating or shooting. They wanted information from him and were hoping to make him feel relaxed and uninhibited.

"So... er... Comrade Ursall." began Hargreaves. "I must apologize for the rather brusque form of this invitation, but we need to speak to you urgently. Could you please tell these comrades exactly what Col. Eveslowe told you last night?" He produced a notebook and pencil from his pocket.

Will took another sip. The vodka was quite high quality, Will thought; way better than the paint stripper dished out to the Red Army. "He told me that the Peasemore laboratory is being run by a contractor, Nash and Wallace."

"We know all that already." interrupted Hargreaves.

"I'm answering your question." responded Will in a cold voice. The vodka had already given him some confidence. "As I was saying, N and W are the owners and operators of the lab in Peasemore. It was established by the War Ministry after the invasion of Lancombe Pond and the retrieval of artefacts from..." His speech ground to a halt.

"Go on." said Otto.

"Artefacts from an extraterrestrial civilization."

His three captors exchanged expressionless looks.

"This confirms the information gained from Francis Ursall, my father; the information I have already given you which you did not believe." He paused to glare at them. "A... spacecraft crashed in Lancombe Pond in 1918. Eveslowe heard about it in a meeting at the War Ministry a couple of years ago. Nobody knows where it's from. The same goes for the biological entity also discovered at the crash site. What Eveslowe then told me was that this was only one of several similar incidents that have taken place over the last several dozen years in theUK United

States

"What did he say?" asked Otto urgently.

"That there was a crash in 1897 at a place calledAurora Texas Washington DC

The men sat back. "What!?" exclaimed Hargreaves. "The cemetery inTexas

"That's what he said. The villagers gave the creature a funeral. It's there right now."

"Did Col. Eveslowe tell you where he heard this information?"

"From a friend of his who was the US Army attaché during the War."

Hargreaves was scribbling in his notebook. "What other incidents does he know about?"

"He appears to have less information about the others. He knows of them primarily through rumours circulating in the Ministry. He mentioned that one happened inIreland

The men made a silent confab again. Otto cleared his throat. "Tell me, why have we not heard about all this in the newspapers?"

Will shrugged. "You'll have to address that question to a newspaper editor, Mr Otto." There was a long pause. The bald man called "Yuri" had not spoken since he'd served the drinks. He stared hard at Will. Will broke the silence: "Comrades, my wife will be wondering where I am by now. We are due at a bridge circle bysix o'clock ."

"We won't detain you any longer than necessary." smiled Hargreaves. "We just ask you for your understanding... You see, what you have been telling us cannot be true, yet we have not detected any disinformation attempts independently of your contribution. We can think of no theoretical purpose for such a thing. So, obviously we are going to feel suspicious of you."

"I can't comment on what makes you feel suspicious, Comrade Hargreaves. You alone are qualified thereof. I have done my job. I have delivered to you the intelligence I have discovered. I don't know whether or not this intelligence is true or false, only that it exists. I am not lying to you, I swear."

They all looked at him darkly.

"Do you really think I am making all this up? Why would I do that?"

"A different loyalty?" answered Otto with a half smile.

Will felt a chill. Those words were a stock phrase in the intelligence community for being a double agent. "Comrades... I am not a traitor!" They continued to sit and stare. "I fought in the civil war!" He started speaking in Russian. "I leftOxford

After another long pause Otto said: "Alright, Comrade Ursall. We have no further questions at this point."

Will was blindfolded again and led back to the car. This time the drive was much shorter. They took off the hood and let him out of the car on an industrial road with warehouses on either side. When he saw the railway station in front of him Will realized he was in Stratford, which meant the safe house he was frogmarched to must be somewhere in the borough or not far beyond. He caught the train home.

"Nobody knows, or at least Eveslowe doesn't." The whole process had taken about a month. Hargreaves gave him additional coaching to select the perfect target. Somebody quite old and senior with military connections, a few personal secrets and as many vices as possible. Col. David Eveslowe had recently retired from the War Ministry and regularly indulged in more than his fair share of brandy and cigars. He had spent twenty years in

"Ah!" Eveslowe puffed on a

"It's a pity we don't have a telescope here, Dave."

"Perhaps we should get one installed in the garden. I'll suggest it to Patel... How many stars can we actually see in the middle of the Smoke anyway? Let's go and have a look." He clambered shakily to his feet. It was now

"What a pity." sighed Will in the same tone. "I love the sight of a clear night's sky, cloudless and pure."

"I know, Wilfred, I know. In

Now was the moment for his next move. "You should be a poet!... I say, Dave... Do you suppose there's anybody out there, looking back at us?"

He laughed. "Oh certainly, old boy!"

"Certainly? You have no doubt?"

Eveslowe looked at him in a fatherly way without desire. "None whatsoever, dear boy. You see... No, no, no; I really can't tell you."

Will put on his best frown of curiosity. "What do you mean, Dave?"

He hissed through his teeth in an intoxicated expression of awkwardness. "We have proof, Wilfred."

"Does this have anything to do with what's going on at Peasemore?"

The old man gasped and took a step back. His face flushed as if Will had struck him. "Wilfred... where did you hear about that?"

He shrugged modestly. "Word gets around."

Hargreaves watched a starling pecking the path near his feet. "And did he tell you more?"

"Yes." Will related some more details for a few minutes.

The controller suddenly stood up. "Let's take a walk, Comrade Ursall."

"What?" Will stood up beside him. This had never happened before. Contact with his controllers had always been stationary and in a public yet secluded place. In fact at the spy school he'd been warned about movement, that it could look suspicious in the wrong circumstances. "Comrade Hargreaves. I think we're supposed to remain seated during our conversations..."

"This is an unusual occasion, Comrade Ursall." Hargreaves lifted his right arm in which he carried a copy of The Times. It was draped over his wrist and was arranged in such a way that only Will could see the pistol clasped in his hand.

"No!" yelled Will and jerked back.

"Keep your voice down and stand still!" commanded Hargreaves in a voice only slightly raised. "Now, walk towards the

Will nodded. He was panting hard and his legs felt weak, but he did what his controller said. A car, a non-descript Morris, was waiting by the gate with two men in the front seats. Its rain cover was up. "Get in." said Hargreaves. The agent and controller sat beside each other in the back seat. Will was about to look at the two other occupants when a hood was roughly tugged over his head totally obscuring his vision. His heavy breathing became more laboured through its textile. "Calm down, Comrade Ursall. You are in no danger."

"Having a gun pointed at me is not exactly safe!" protested Will.

"Sorry about that, comrade; it was necessary." The car drove for about half an hour although, of course, Will could not be completely sure of the time. At one point Will heard the ambient sounds that leaked in change in a way that gave him the impression they were crossing one of the bridges over the river. He hoped they were heading for the Soviet embassy in Kensington, in which case this would be a happier situation. On the other hand this action against him by his handlers could be something less official and therefore probably more violent. This was exactly what Will had feared. They had tested him and he'd failed. The worst part was that he knew he was innocent. Could he persuade them? He was afraid they would torture him, in which case he knew that he would eventually say anything they wanted him to. Or maybe they had already made up their minds, in which case...

"Alright, we're there." said a new voice from the front seat. The car turned a few times and then stopped. "Let me guide you, comrade." said Hargreaves. Will got out of the car with the blindfold still over his head and walked with Hargreaves holding his arm. "There are four steps up here... That's it." A few yards further the handler ordered him to sit.

Hargreaves pulled off the hood and all Will's senses were assailed at once. He was sitting at a small wooden table in an office of some kind. There was a cardboard calendar on the wall, a filing cabinet and a pair of desks facing each other. The wall was painted dark brown and the windows looked out onto a street with a red brick wall opposite, although Will couldn't make out many of the details until his eyes had adjusted to the glare. Sitting around the table scrutinizing him were Hargreaves, Otto and a third man whom Will had never before seen. Hargreaves had laid the pistol on the table, but his hand rested on it; a silent warning to Will not to try and flee. Despite the nature of his presence there, the men were all smiling. "Would anybody like some vodka?" asked the stranger. He had a Russian accent and a big bald military look to him.

"Four glasses please, Yuri." replied Otto. After the drinks were all poured he raised his. "Vashe zdorov'ye."

"An kkomyt." Will replied and took a sip. He felt calmer now and slightly rebellious. He had learned enough at spy school to realize now that these men would not do him any grievous bodily harm, at least not at this meeting. A round of vodka meant a little chat, not a beating or shooting. They wanted information from him and were hoping to make him feel relaxed and uninhibited.

"So... er... Comrade Ursall." began Hargreaves. "I must apologize for the rather brusque form of this invitation, but we need to speak to you urgently. Could you please tell these comrades exactly what Col. Eveslowe told you last night?" He produced a notebook and pencil from his pocket.

Will took another sip. The vodka was quite high quality, Will thought; way better than the paint stripper dished out to the Red Army. "He told me that the Peasemore laboratory is being run by a contractor, Nash and Wallace."

"We know all that already." interrupted Hargreaves.

"I'm answering your question." responded Will in a cold voice. The vodka had already given him some confidence. "As I was saying, N and W are the owners and operators of the lab in Peasemore. It was established by the War Ministry after the invasion of Lancombe Pond and the retrieval of artefacts from..." His speech ground to a halt.

"Go on." said Otto.

"Artefacts from an extraterrestrial civilization."

His three captors exchanged expressionless looks.

"This confirms the information gained from Francis Ursall, my father; the information I have already given you which you did not believe." He paused to glare at them. "A... spacecraft crashed in Lancombe Pond in 1918. Eveslowe heard about it in a meeting at the War Ministry a couple of years ago. Nobody knows where it's from. The same goes for the biological entity also discovered at the crash site. What Eveslowe then told me was that this was only one of several similar incidents that have taken place over the last several dozen years in the

"What did he say?" asked Otto urgently.

"That there was a crash in 1897 at a place called

The men sat back. "What!?" exclaimed Hargreaves. "The cemetery in

"That's what he said. The villagers gave the creature a funeral. It's there right now."

"Did Col. Eveslowe tell you where he heard this information?"

"From a friend of his who was the US Army attaché during the War."

Hargreaves was scribbling in his notebook. "What other incidents does he know about?"

"He appears to have less information about the others. He knows of them primarily through rumours circulating in the Ministry. He mentioned that one happened in

The men made a silent confab again. Otto cleared his throat. "Tell me, why have we not heard about all this in the newspapers?"

Will shrugged. "You'll have to address that question to a newspaper editor, Mr Otto." There was a long pause. The bald man called "Yuri" had not spoken since he'd served the drinks. He stared hard at Will. Will broke the silence: "Comrades, my wife will be wondering where I am by now. We are due at a bridge circle by

"We won't detain you any longer than necessary." smiled Hargreaves. "We just ask you for your understanding... You see, what you have been telling us cannot be true, yet we have not detected any disinformation attempts independently of your contribution. We can think of no theoretical purpose for such a thing. So, obviously we are going to feel suspicious of you."

"I can't comment on what makes you feel suspicious, Comrade Hargreaves. You alone are qualified thereof. I have done my job. I have delivered to you the intelligence I have discovered. I don't know whether or not this intelligence is true or false, only that it exists. I am not lying to you, I swear."

They all looked at him darkly.

"Do you really think I am making all this up? Why would I do that?"

"A different loyalty?" answered Otto with a half smile.

Will felt a chill. Those words were a stock phrase in the intelligence community for being a double agent. "Comrades... I am not a traitor!" They continued to sit and stare. "I fought in the civil war!" He started speaking in Russian. "I left

After another long pause Otto said: "Alright, Comrade Ursall. We have no further questions at this point."

Will was blindfolded again and led back to the car. This time the drive was much shorter. They took off the hood and let him out of the car on an industrial road with warehouses on either side. When he saw the railway station in front of him Will realized he was in Stratford, which meant the safe house he was frogmarched to must be somewhere in the borough or not far beyond. He caught the train home.

The doorbell rang the following Saturday morning just after 9 AM . Will was still in his dressing gown with a

slice of toast in his hand as he walked up to the door. Through the frosted

glass of the door window he recognized a police uniform. He froze; not in fear,

he knew Lareen and Annabelle were safe because they were in the kitchen a dozen

feet from him. Had somebody he knew been involved in an accident? What if...?

He almost yelped aloud. Was it something to do with his abduction a few days

ago? He continued forward and opened the door. A single officer stood in front

of him in a black tunic and custodian helmet. "Good morning, sir. Sorry to

bother you. PC Blaine, Herts constabulary. We've been asked by the Lancombe

Pond force to help investigate a missing person."

"Who?"

The man looked at a notebook. "A Mrs Loyl Ursall. Do you know her, sir?"

"Yes of course. She's my grandmother?... You'd better come in."

"Thank you, sir." The policeman took off his helmet as he entered the vestibule of the house. "Mrs Ursall was reported missing two weeks ago by some friends after she had failed to attend a Spiritualist meeting several times in a row. Inquiries at her home indicated that she had been absent for several weeks before that."

Will told the officer about his recent visit to his grandmother's house.

The policeman scrawled in his notebook with a short and solid graphite pencil. "I see, so she had packed her bags."

"She told me she was going to Skegness for a few days... Come to think of it, she was acting strangely."

"And this gentleman you saw her with; do you know anything about him?"

"No, except he worked at the main hospital inNottingham and that my

brother was very close to him. You'd be better off talking to him."

"Oh, we will, sir." replied the man. "Does the name 'Dirk Walsander' mean anything to you?"

"No, except it sounds Dutch. That might have been his name, if I recall."

"We believe that is the name of the man who went too see your granny, sir."

"So, presumably if he and my grandmother went on holiday together you'll find them together now."

"A very long holiday though, isn't it, sir?"

Will nodded.

"It may interest you to know that we have it on good authority that Mrs Ursall and Mr Walsander were seen boarding a train together inLondon

"Well... they may have been going there to catch the ferry. My family have done that many times because of our Dutch relations. My mother was..."

"They were indeed, sir. In fact we had a call from the British embassy in theNetherlands Hook of

Holland on September the 20th... Do you know of any reason why

your grandmother might abscond abroad with a strange man without telling her

family?"